The year was 1992, but Rex Sinquefield and David Booth, founders of mutual fund company DFA, were feeling trapped in the ‘80s. Rex was still wearing parachute pants and neon ties, and David drove a Pontiac Fiero and had White Snake and Mötley Crüe posters taped to his office walls.

Worse (depending on your opinion of White Snake), their flagship small cap fund had consistently underperformed the stock market through the 1980s.

“Hey man,” said Rex, handing David a Betamax tape with a pirated copy of Top Gun, “we’ve got to reinvent ourselves. Move forward.”

“Thanks for the tape” David replied, “One step ahead of you. Take a look at this.”

And with that he handed Rex a study that changed everything at DFA. It was a research paper called “The Cross‐Section of Expected Stock Returns”, and it was written by academics Eugene Fama and Ken French. The paper showed that differences in size and book value explained most of the variation in equity returns. The smaller the company, and the more book value it had, the better it seemed to perform.

Stocks with a relatively high book value became known as “value” stocks, and those with low book value became known as “growth” stocks.

Notably, the study showed that almost all the returns from the small cap stocks DFA was selling came from the group with a high book value. In fact, small growth stocks had, according to the Fama/French data, 0% returns over the past seven decades! Fama and French speculated that the excess returns of small and value stocks came from excess risk, though they couldn’t identify how.

DFA stands for “Dimensional Fund Advisors”, but DFA had only one stock “dimension” between its founding in 1981 and 1992 – company size. See my last post for details. The Fama/French paper showed how adding a second filter, for value stocks, might improve returns.

In 1993, DFA launched its small value fund, DFSVX, which owned only those stocks that Fama/French data said would produce fantastic returns – far more than the mere 5% per year bonus Sinquefield had claimed for small caps. DFA launched a number of value funds in the early ’90s: small value, large value and international value (large and small).

DFA stock funds were now two dimensional, and a new era had dawned. Rex discovered Pearl Jam and got rid of his earring. David amassed an amazing collection of Beanie Babies, though he never got Tigs the giraffe, which rumor has it he’s still hunting for on ebay.

Where were we? DFA likes to keep the academics whose research it follows comfortably on the payroll – you’d hate to have your marketing strategy upended by some unaffiliated professor who’d changed his mind or revised his data. And in fact, Eugene Fama, co-author of the study, had been on the DFA payroll for years as a part-time trader.

In co-opting their research into a marketing campaign, however, DFA took this to a new level, making Fama and French equity partners in the firm, and, over time, very rich.

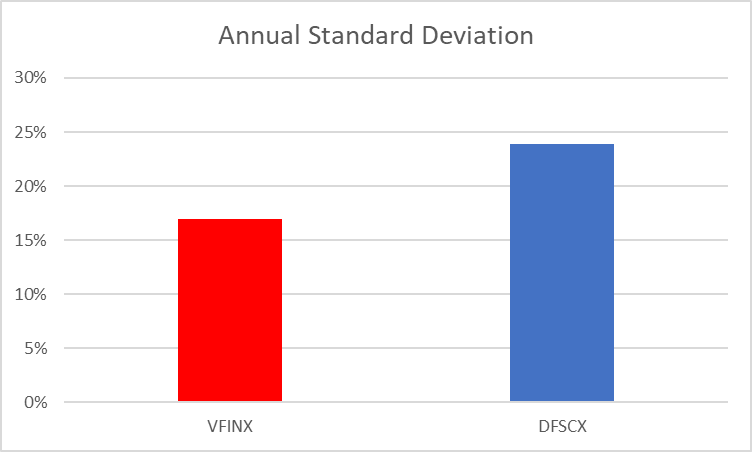

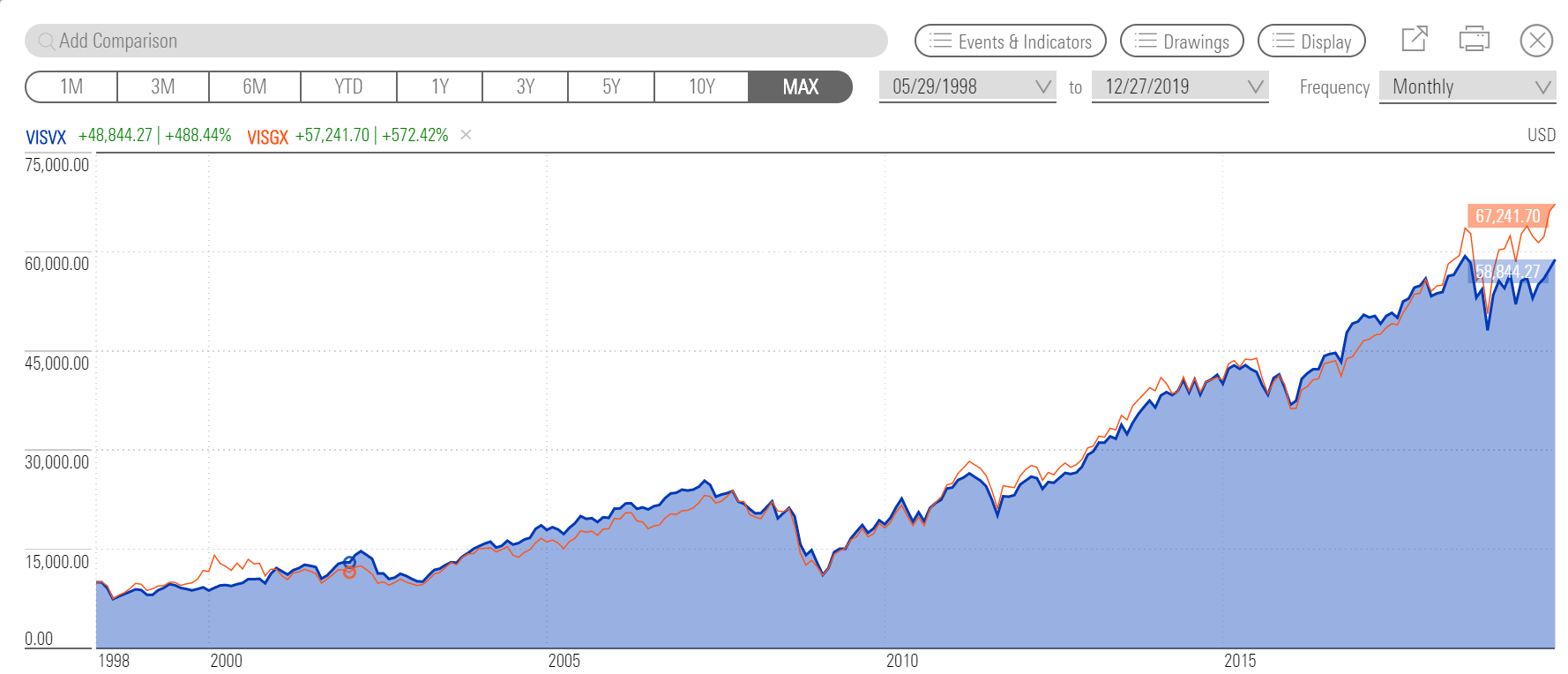

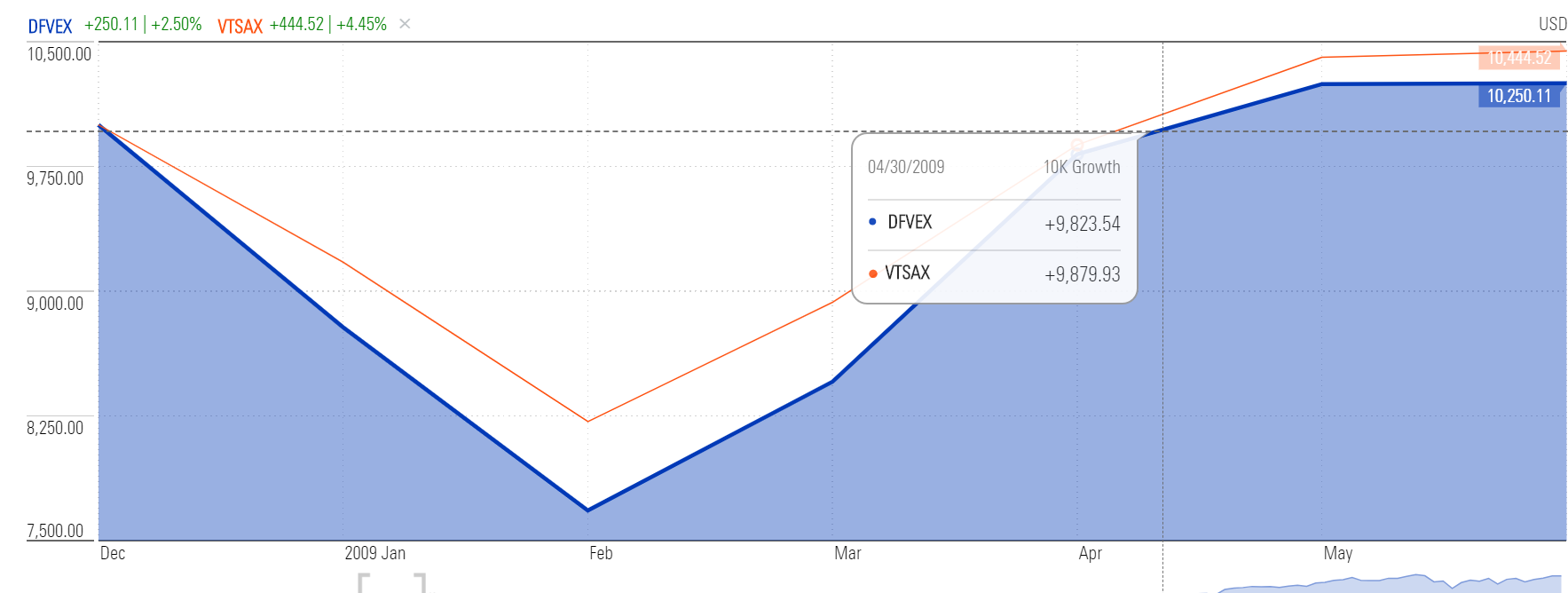

We now have over 27 years of data to judge whether the incredible returns promised by Fama and French materialized for investors. First though, let’s look at risk. We’ll compare DFSVX to the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index fund (VTSAX). All data here from Morningstar:

As with the DFA Small Cap fund, the DFA small value fund exhibits large amounts of volatility versus the market as a whole. If you like wild swings in your portfolio value, DFSVX is for you.

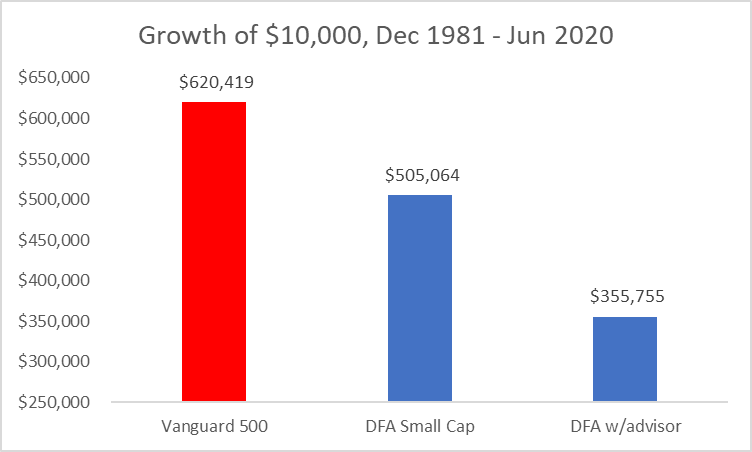

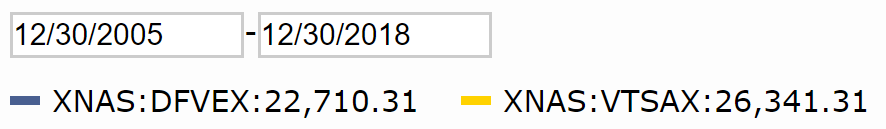

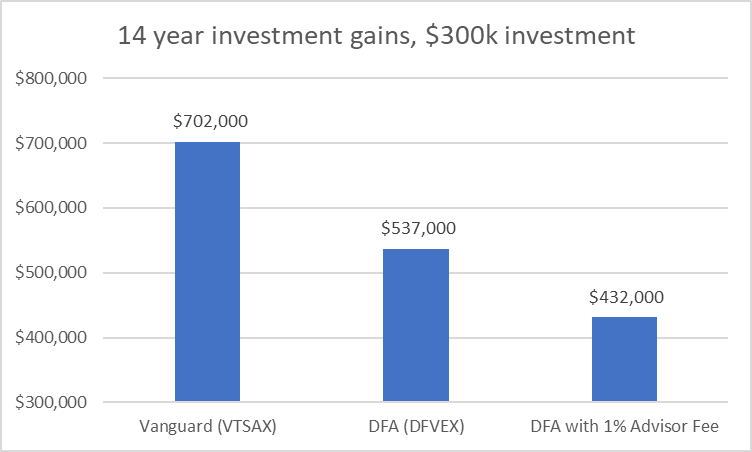

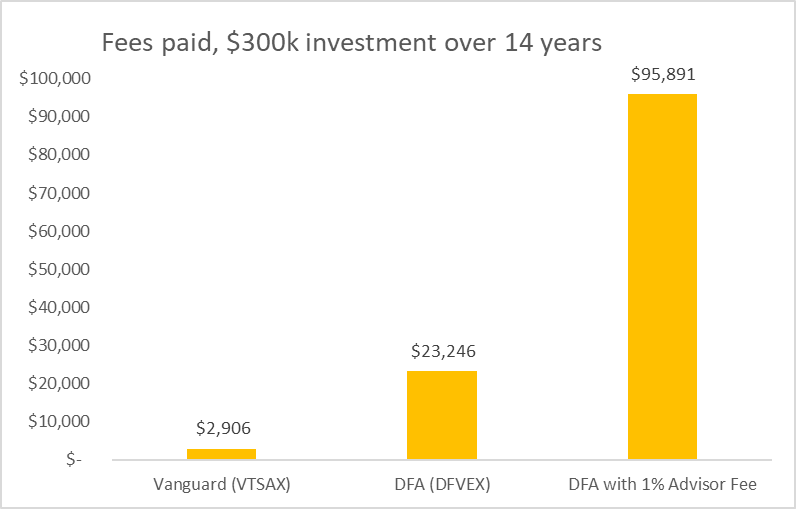

Did investors get the amazing market beating returns promised, or at least strongly implied, by DFA? As always, I also show returns for the DFA fund including a 1% advisor fee, since paying an advisor is the only way to access their funds. The chart below shows the growth of a $10,000 investment in both the DFA and Vanguard funds on the day the DFA fund began trading in 1993 through today:

This one’s a tie – the DFSVX and VTSAX have had the same 9.5% average annual return. Stunningly, investors didn’t get even a penny of the amazing excess profits promised by the Fama/French data. In fact, they came out far behind Vanguard due to the advisor fee layer.

What happened here? For that, I’ll refer you to my last post about the DFA flagship fund, DFSCX, as the problems are the same. The first is cost – even without the advisor fee, the expense ratio of this fund is .5% higher than Vanguard’s.

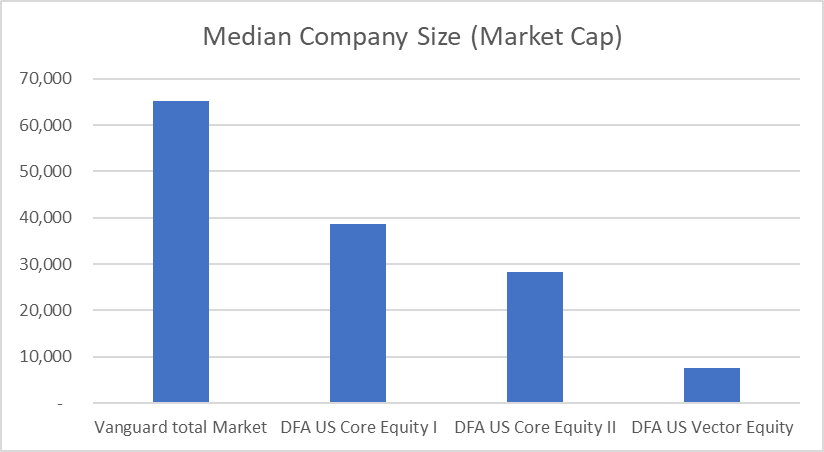

The second is that academic data just doesn’t translate into real world fund results – the few, tiny, highly value-y stocks that accounted for the bulk of the Fama/French returns are too small and illiquid to be held in a consumer mutual fund.

David and Rex didn’t produce the returns they promised investors. But they had a had a hell of a ride, and made a ton of money. Sometimes they think about getting together and heading out for a night on the town. But they’re old now, in different states. They email. The other day Rex sent David his favorite quote from the ‘80s movie Risky Business, which he still has on Betamax:

It was great the way her mind worked. No guilt, no doubts, no fear. None of my specialties. Just the shameless pursuit of immediate gratification. What a capitalist.